The first stages of a project are the foundation on which the whole design process will either stand or fall; investing adequate time at this stage is crucial if the project is to have every chance of success. Spending time to make sure that each aspect of the project is properly identified will deepen your understanding of the task ahead, and will open up new avenues for exploration as the design evolves.

Teasing out information from a brief can be a long process and isn’t always fulfilling in itself, but it allows you to research and formulate a concept, and strong concepts (key ideas) are what the most successful projects have at their heart. There are several steps to achieving your goal of understanding the project, from meeting the client and taking a brief from them, to developing a concept. Each step is looked at in more detail in this chapter.

The client

Clients can be anyone from anywhere. A client might just as easily be a company or organisation as an individual. However, as clients, they all have a common need for the services of an interior designer, though the level of understanding of these needs is likely to vary greatly between them.

For some, the decision to engage a professional designer will have been arrived at after a careful appraisal of their circumstances. For others it will be a vague idea that there is likely to be someone (the designer) who can provide better answers to their problem than they would be able to do themselves. Some clients may believe that aesthetics are the main issue and the practical side of their needs may not have featured in their decision to call in the designer at all. For others, practicalities may be the prime consideration, with decorative concerns a secondary issue.

It is for these reasons, and many others, that the designer needs to be able to communicate on many levels with lots of different personality types. From the forthright to the timid, clients need to be understood, treated with respect and made to understand that they are a key element of the design process.

Because you will often be trying to connect with a client on an emotional level, establishing a good rapport is a must. In fact, it is sometimes a more important part of building a good client / designer relationship than being able to provide an extensive curriculum vitae.

Client profile

The client profile is an attempt to understand better who the client is and how they live or work. It is a general overview and while in itself it may not relate directly to the brief that the client has given, it will provide insights that will help you as you develop your design.

In a residential project, the client profile can help you to understand how the space might be used on a daily basis from first thing in the morning until last thing at night, and it may also give some clues as to style preferences of the client. An understanding of the daily routine can be one of the most vital parts of producing a design that works for the client.

For commercial projects, understanding the work practices of the organisation that will ultimately occupy the space is essential. This is another opportunity to look closely at the status quo and determine if the existing work patterns make best use of the space. You may find that they do, or you may be able to challenge these and propose new and better ways of working. Commercial clients often employ designers not just to create comfortable working environments, but as ‘agents of change’ when they know that a new direction will benefit their organisation.

The briefing

The briefing is the first real chance that you will have to get a feel for a project. Some briefs are presented to you by the client as carefully constructed documents that fully convey the scope and detail of the project; other briefs may be little more than a casual chat over a cup of coffee.

Although a written brief is likely to contain a good deal of useful information, quantity by itself does not necessarily mean quality. In 1657, French mathematician, physicist and philosopher Blaise Pascal wrote, ‘I have made this letter longer than usual, only because I have not had the time to make it shorter.’ Information that is succinct and relevant is the essence of a successful briefing document. In fact, brevity is often a good thing. If the brief is focussed and clear, it will be easier for the designer to make incisive decisions and to formulate an effective design solution.

Understanding the brief

It is quite reasonable to ask the client to produce a written brief after their initial contact with you, and prior to the briefing meeting. This is a good tactic because it will force the client to carefully consider their request, and it will also make sure that they are serious about the idea of engaging an interior designer. The chance to talk about the writ en brief at a later date will allow both parties to sort out any problems or uncertainties that arise from it. The opportunity for mutual agreement is one that should be made the most of; time spent talking over the brief will give both sides a better understanding of each other’s position and can only have a positive effect on the business relationship.

The more complete the brief, the easier your job should be, but you should remember that you may be dealing with amorphous feelings and ideas about the desired end point of a project, rather than a definitive list of needs. It ’s entirely possible that the ‘brief ’ may consist of the client saying no more than, ‘I just want somewhere that ’s a great place to come back to after a hard day’s work’.

Even if the brief is vague, and whatever the practical requirements of it may be, there will be some constraints that you should try to establish: time and budget available, aesthetic style, the scope of project. Constraints, particularly heavy ones, can actually be good. Try to see them not as limiting the project, but helping to define it. Once you know some of these constraints, you can plan more effectively, discarding options that fall outside the boundaries and concentrating on those options that will fit the brief.

Many projects, whether domestic or commercial, will have more than one individual as the client. You should try to make sure that, whoever has writ en the brief or whoever you have spoken to in your meetings, the final brief has been agreed by everyone who has a stake in the finished project. You also need to take the opportunity at face-to-face meetings to be certain that you and the client understand each other explicitly; what does the client think of when they say ‘contemporary’? Is their understanding of the word the same as yours? This is the time to find out.

Careful consideration has been given to the functions required of this room in the Homewood in Esher, England. The tubular steel leg of the bar folds under the bar top to allow it to pivot back into a wall that also contains storage for other items and a pass-through hatch to the kitchen.

Design analysis

Having met the client and taken a brief, the detailed analysis can begin. You need to be sure that you understand all that the client needs. Sometimes this will have been explicitly stated, at other times you will have to make inferences from the information that you have.

Collecting information

You also have to perform a careful balancing act with the raw information. Your judgement will be crucial in deciding whether the client has actually understood their own needs. Remember that clients have engaged you because they believe that they need a professional, which implies that they are not experts, so some of the assumptions they have made may not be correct and it will be down to you to put them right. If you were to produce a finished design solution where you had managed to ‘tick all the boxes’ they ought to be content with the solution provided. But ‘content’ is not what you should be aiming for. Something extraordinary, even revolutionary, can often only be realised when you don’t simply provide the client with the answer that they think they need. Special things happen when insight leads to turning an idea on its head, or doing something contrary to what the client is expecting, or doing it in a way that hasn’t been done before, will answer the brief in a better, more efficient or more beautiful way. Unusual ideas will need to be thoroughly tested and resolved during the later development stages of the design process to ensure that they really do work, but it ’s these ideas that will yield a delighted client, not just one who is ‘content’.

With the brief, some clients include practical issues that need to be addressed. Others may talk in general, abstract terms about the emotional response that they want their space to trigger. Even if the brief is vague, there will be some constraints that you can establish: time, budget, style and so on. The word ‘constraint’ sounds negative, but you should actively be trying to seek out the constraints present in the brief. Constraints are actually good. You should look at them as a positive force within the design analysis that will help you help you define the scope of the project. When a brief seems complex or daunting, the natural constraints can be some of the first elements that help you see the shape of the project.

This composite image has been produced as part of the research into the site. It consists of several prints that have been roughly collaged together, and in itself provides an evocative sense of the location of the project. It serves as a reference for colour and style.

Question the brief

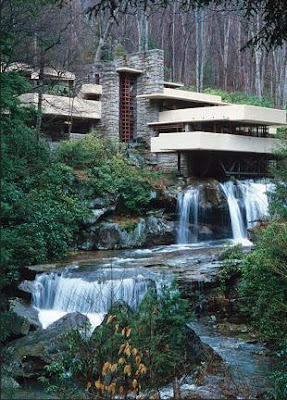

What is arguably one of the most iconic buildings in the world owes its form and success to an architect who didn’t hesitate to question the brief. The building is Fallingwater, by Frank Lloyd Wright at Bear Run, Pennsylvania, USA.

The client, Edgar J Kaufmann, took Wright to his site at Bear Run where he wanted to build a summer house. With broadleaf trees and rhododendron bushes all around, the site overlooked the river at a point where it cascades over a waterfall. At the same time, Kaufmann also gave Wright a survey of the site which he had commissioned some time earlier. This site survey drawing showed the river towards the northern part of the site, the waterfall, and the hillside to the south of the waterfall. It was clear from the way that the site plan had been laid out that Kaufmann expected to build his house on the hillside south of the river. From this situation, there would be a view of the waterfall

to the north. However, Wright wasn’t content with this interpretation of the landscape. Instead, without any consultation with the client and using the new technology of reinforced concrete, The proposed a design for the house that integrated it completely into the site by using a cantilever construction to launch the house out over the river, above the waterfall, from the northern hillside. Wright said to Kaufmann ‘I want you to live with the waterfall, not just look at it, but for it to become an integral part of your lives.’ In so doing he created the building for which he is probably best known, and he gave his client an experience of and an involvement with the site far beyond what was originally anticipated.

For one of his most iconic buildings – Fallingwater in Pennsylvania, USA – Frank Lloyd Wright proposed a design that boldly questioned his client’s brief. Rather than situate the house away from the waterfall, he decided to integrate it completely into the site.

Analysing information

It ’s easy to imagine that ‘analysis’ means an intellectual and academic dissection of the data from the brief. This is a factor of most analyses, but it can be a visual exercise as well as a literary one. You are, after all, going to be exploring the aesthetic side of the brief in addition to the practical, and working visually with media such as collage, sketching and photography will help you form links and develop aesthetic ideas in a free and potentially unrestricted way. This style of working is a fast and efficient way for a creative mind to access new ideas as they emerge from the brief, and it connects well with the building and site research that will be looked at later. Ultimately, if you are to produce an effective analysis, you should feel able to work in any way or medium that makes you feel comfortable. This is a skill that may need practice, but it is also a rewarding one that pays dividends

Two well recognised techniques that can help in the process of analysis and evaluation are brainstorming and mind-mapping. Brainstorming is an activity designed to generate a large number of ideas, and is usually undertaken as a group activity, but there is no reason why the principles should not be applied to solo sessions. Four basic rules underpin the process:

- Quantity of ideas is important; more ideas equate toa greater chance of finding an effective solution.

- Ideas are not criticised, at least not in the early stages of the exercise – that can come later when all the ideas have been generated. Ideas that might have some drawbacks could be built on to produce stronger ideas.

- Unusual, of -beat ideas are encouraged. They may suggest radical new ways of solving a problem.

- Ideas can be combined to produce better solutions.

Mind maps are diagrams that are used to visually represent ideas and associations surrounding a central thought or problem. There is no formal method for organising the map, instead it grows organically and allows the designer to arrange and link the information in any way that feels right, though the different points are naturally organised into groups or areas. Pictures, doodles and colour are as much a part of a mind map as are words; imagery helps to reinforce ideas and the visual pattern created is easier for the brain to process and contemplate than a simple list, encouraging subconscious processing of the information at some later point.

Once you are satisfied that you have extracted as much information from the brief as you can, you will have a secure foundation upon which to build your project research, which is detailed in the following sections.

This mind map was created for a refurb project. The visual and non-linear format of mind maps helps the generation of new ideas and enables connections to be seen easily.

No comments:

Post a Comment