Besides familiarising yourself with the plan form of the space, you should try to make yourself aware of the methods used in the construction of the building. Understanding construction is not simply an academic exercise; knowing how a building is put together is a lesson in possibilities. Once you have a good idea of the structure you will find it easier to make decisions relating to the implementation and practicality of your design work, especially when looked at it in conjunction with the constraints incumbent upon the project, be they time, budget, legal or technical.

A study of building construction will oft en change the way you look at buildings that you use on a daily basis, and an enquiring eye is a very useful skill to develop. The knowledge that you gain by looking at structures will add greatly to your projects and, just as importantly, being able to speak with a degree of confidence about structure will give you credibility with contractors and clients alike. Unfortunately, details of the building structure are oft en hidden away underneath surface finishes and detailing. In the absence of definite information regarding its construction, experience will help you make some reasonable assumptions or deductions about the building.

Building construction principles

As previously described, all buildings are subject to various forces that must be resisted if the building is not to collapse. Although the first structures in history were built through intuition rather than any theoretical understanding, they used many of the same principles that underpin building construction today.

Essentially, the structure of almost every building can be described in one of two ways; they are either frame or load-bearing. These two terms describe how the loads that the building experiences are transmitted to the foundations.

Framed structures

Framed structures are essentially a collection of horizontal beams (forming each floor level) that transmit forces to vertical columns. These columns in turn provide a pathway through which the forces can travel downwards to the foundations and from there into the ground. The vertical columns may form the walls at the perimeter of the building, or they may be distributed throughout the space. Where they are part of a wall structure, they will be covered with suitable materials to create the finished walls. When positioned within the space, two or more columns may be joined to create internal divisions, or they may be left as discrete columns. The great benefit of this multi-level framework is that, because the columns are transmitting the loads vertically, solid-wall structures are not needed to support the floors above, and can therefore be omitted (creating large open-plan spaces punctuated by the supporting columns), or walls can be created using nonstructural materials such as glass. Framed structures allow us to build high-rise buildings that are oft en characterised by facades apparently composed entirely of glass, though the materials used for these curtain walls (that are mechanically suspended off the frame) can be practically anything. Radical architects of the Bauhaus movement in Germany in the 1920s first conceived the use of glass in this innovative way. Because of the strength of frames, buildings can be made very tall. It was the development of framed structures in the latter part of the nineteenth century that lead to the first high-rise buildings.

If the internal divisions are not carrying any load (other than their own weight), they can be moved or altered without the need for any significant interventions to the surrounding structure in order to maintain its integrity. For the designer, therefore, framed structures can give a lot of freedom in planning spaces.

Framed structures do not need to be large scale. The principle can just as easily be applied to houses as it can to skyscrapers. Lightweight timber frames are a common method of construction in many regions of the world, though the frame is usually invisible under a skin or veneer of other materials such as timber weatherboarding or brick. Frames of this type will usually be braced to prevent twisting by the addition of a plywood skin to the outside of the frame. Timber framing of residential developments allows fast and accurate construction by a relatively low-skilled workforce, as it is an easy material to work with. Sections of the frame are oft en pre-fabricated off site under good working conditions, then brought to the site for rapid assembly.

Timber frames are also an environmentally acceptable construction method, assuming that the timber used is from a sustainable source. Highly energy-efficient buildings can be made by inserting insulation between the vertical and horizontal timbers, creating buildings that perform extremely well in some of the most extreme climates, such as the northern hemisphere winters of Canada and Scandinavia. Light frames can also be made from thin section steel, galvanised to prevent corrosion. The internal face of the frame can be very easily covered in plasterboard or other materials to provide a surface suitable to receive decorative finishes.

Load-bearing structures

In a load-bearing structure, it is the masonry construction of the walls themselves that takes the weight of the floors and other walls above. The walls therefore provide the pathways through which forces travel down the structure to the foundations. There is no separate constructional element of the building to do this, as with the frame in a framed structure. The implication of this is that care must be taken when adapting existing load-bearing elements of a structure, if the integrity is not to be compromised. If changes are made to the structure without adequate precautions being made, then the structure will at best be weakened, and at worst collapse.

If it is desired to move door or window positions, or make new openings in a wall for whatever reason, then the loads that are being supported by the wall must be diverted to the sides of the opening to prevent collapse. This is usually achieved by the insertion of a beam or lintel at the top of the opening. This lintel will carry the loads travelling through the wall into the structure at the side of the opening, from where they will travel downwards and so maintain the integrity of the structure. The beam or lintel itself will need to be adequately supported at both ends within the remaining structure. A lintel is a single, monolithic, component and can be manufactured from any suitable material; timber, stone, concrete (either reinforced or pre-stressed) or steel are the most common. Pre-stressed concrete lintels can span considerable distances, as can rolled steel joists (RSJs), which are oft en used in renovation work to allow the removal of internal walls by supporting of the structure above.

If greater distances need to be spanned, it may be more appropriate to construct an arch rather than use a lintel, and this was certainly true before new technologies allowed the use of steel and concrete. Because of their superior mechanical properties, arches can generally support greater loads than lintels. An arch is considered as a single unit, but unlike a lintel it can be composed of a number of shaped components (usually stone or brick, called voussoirs), though it too can be monolithic, like a lintel. Once the individual elements of the arch are in place, the compressive forces (weight) of the building materials above hold them together. The simplest shape of arch is the round or semicircular arch, but there are many variations of form, even fl at arches (sometimes called jack arches). Arch construction is a very practical engineering solution to the problem of spanning openings that are oft en treated as decorative elements of a building’s facade.

Variations

Although the principles outlined above are relatively simple, experience will soon show that there are many variations on these themes that are used throughout construction. Manufacturers develop new methods and interpretations of existing solutions and the desire of architects to challenge existing ideas of what a building is mean that these techniques soon become feasible. Changes to building regulations and codes for reasons of fire safety, tougher acoustic performance, reduced environmental impact and so on, all mean that there is a need for new building practice. Details change but the principles remain the same. With experience, it becomes easier to discern the theory behind the construction, but it is worth bearing these complexities in mind when looking at building structure.

A study of building construction will oft en change the way you look at buildings that you use on a daily basis, and an enquiring eye is a very useful skill to develop. The knowledge that you gain by looking at structures will add greatly to your projects and, just as importantly, being able to speak with a degree of confidence about structure will give you credibility with contractors and clients alike. Unfortunately, details of the building structure are oft en hidden away underneath surface finishes and detailing. In the absence of definite information regarding its construction, experience will help you make some reasonable assumptions or deductions about the building.

Building construction principles

As previously described, all buildings are subject to various forces that must be resisted if the building is not to collapse. Although the first structures in history were built through intuition rather than any theoretical understanding, they used many of the same principles that underpin building construction today.

Essentially, the structure of almost every building can be described in one of two ways; they are either frame or load-bearing. These two terms describe how the loads that the building experiences are transmitted to the foundations.

Framed structures

Framed structures are essentially a collection of horizontal beams (forming each floor level) that transmit forces to vertical columns. These columns in turn provide a pathway through which the forces can travel downwards to the foundations and from there into the ground. The vertical columns may form the walls at the perimeter of the building, or they may be distributed throughout the space. Where they are part of a wall structure, they will be covered with suitable materials to create the finished walls. When positioned within the space, two or more columns may be joined to create internal divisions, or they may be left as discrete columns. The great benefit of this multi-level framework is that, because the columns are transmitting the loads vertically, solid-wall structures are not needed to support the floors above, and can therefore be omitted (creating large open-plan spaces punctuated by the supporting columns), or walls can be created using nonstructural materials such as glass. Framed structures allow us to build high-rise buildings that are oft en characterised by facades apparently composed entirely of glass, though the materials used for these curtain walls (that are mechanically suspended off the frame) can be practically anything. Radical architects of the Bauhaus movement in Germany in the 1920s first conceived the use of glass in this innovative way. Because of the strength of frames, buildings can be made very tall. It was the development of framed structures in the latter part of the nineteenth century that lead to the first high-rise buildings.

If the internal divisions are not carrying any load (other than their own weight), they can be moved or altered without the need for any significant interventions to the surrounding structure in order to maintain its integrity. For the designer, therefore, framed structures can give a lot of freedom in planning spaces.

Framed structures do not need to be large scale. The principle can just as easily be applied to houses as it can to skyscrapers. Lightweight timber frames are a common method of construction in many regions of the world, though the frame is usually invisible under a skin or veneer of other materials such as timber weatherboarding or brick. Frames of this type will usually be braced to prevent twisting by the addition of a plywood skin to the outside of the frame. Timber framing of residential developments allows fast and accurate construction by a relatively low-skilled workforce, as it is an easy material to work with. Sections of the frame are oft en pre-fabricated off site under good working conditions, then brought to the site for rapid assembly.

Timber frames are also an environmentally acceptable construction method, assuming that the timber used is from a sustainable source. Highly energy-efficient buildings can be made by inserting insulation between the vertical and horizontal timbers, creating buildings that perform extremely well in some of the most extreme climates, such as the northern hemisphere winters of Canada and Scandinavia. Light frames can also be made from thin section steel, galvanised to prevent corrosion. The internal face of the frame can be very easily covered in plasterboard or other materials to provide a surface suitable to receive decorative finishes.

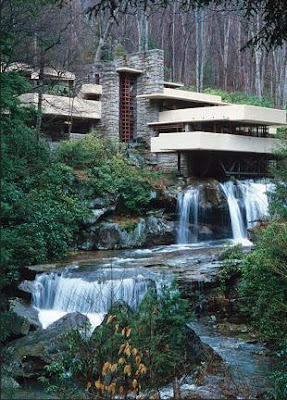

The framed structure of The Farnsworth House by Mies van der Rohe in Plano, USA, is clearly evident and is a major visual feature of this iconic design. It is considered by many to be one of the most beautiful buildings ever designed.

Load-bearing structures

In a load-bearing structure, it is the masonry construction of the walls themselves that takes the weight of the floors and other walls above. The walls therefore provide the pathways through which forces travel down the structure to the foundations. There is no separate constructional element of the building to do this, as with the frame in a framed structure. The implication of this is that care must be taken when adapting existing load-bearing elements of a structure, if the integrity is not to be compromised. If changes are made to the structure without adequate precautions being made, then the structure will at best be weakened, and at worst collapse.

If it is desired to move door or window positions, or make new openings in a wall for whatever reason, then the loads that are being supported by the wall must be diverted to the sides of the opening to prevent collapse. This is usually achieved by the insertion of a beam or lintel at the top of the opening. This lintel will carry the loads travelling through the wall into the structure at the side of the opening, from where they will travel downwards and so maintain the integrity of the structure. The beam or lintel itself will need to be adequately supported at both ends within the remaining structure. A lintel is a single, monolithic, component and can be manufactured from any suitable material; timber, stone, concrete (either reinforced or pre-stressed) or steel are the most common. Pre-stressed concrete lintels can span considerable distances, as can rolled steel joists (RSJs), which are oft en used in renovation work to allow the removal of internal walls by supporting of the structure above.

If greater distances need to be spanned, it may be more appropriate to construct an arch rather than use a lintel, and this was certainly true before new technologies allowed the use of steel and concrete. Because of their superior mechanical properties, arches can generally support greater loads than lintels. An arch is considered as a single unit, but unlike a lintel it can be composed of a number of shaped components (usually stone or brick, called voussoirs), though it too can be monolithic, like a lintel. Once the individual elements of the arch are in place, the compressive forces (weight) of the building materials above hold them together. The simplest shape of arch is the round or semicircular arch, but there are many variations of form, even fl at arches (sometimes called jack arches). Arch construction is a very practical engineering solution to the problem of spanning openings that are oft en treated as decorative elements of a building’s facade.

Renovation of this load-bearing structure (a traditional Victorian terraced house in London) required the introduction of supporting rolled steel joints (RSJs) in order to allow the removal of internal load-bearing walls. Here the steel beams are being brought into the house through the front window.

Variations

Although the principles outlined above are relatively simple, experience will soon show that there are many variations on these themes that are used throughout construction. Manufacturers develop new methods and interpretations of existing solutions and the desire of architects to challenge existing ideas of what a building is mean that these techniques soon become feasible. Changes to building regulations and codes for reasons of fire safety, tougher acoustic performance, reduced environmental impact and so on, all mean that there is a need for new building practice. Details change but the principles remain the same. With experience, it becomes easier to discern the theory behind the construction, but it is worth bearing these complexities in mind when looking at building structure.

In the same London house, the RSJ (painted red) can be seen during its installation into the floor space. This has necessitated the trimming and re-attachment of several floor joists. A structurally simpler, but aesthetically less pure, solution would have involved fitting the RSJ below the existing floor joists.